SANTA FE, N.M. (AP) — The investigation into the death of Gene Hackman, his wife and dog has found no signs of foul play or gunshot or other wounds, and the gas company is assisting with the probe in a sign that authorities could suspect carbon monoxide poisoning is to blame.

The couple and their dog were found dead during a wellness check Wednesday in their New Mexico home, authorities said Thursday.

Foul play isn't suspected, but authorities haven't disclosed how they died and said an investigation was ongoing.

Hackman, 95, Betsy Arakawa, 63, and their dog were all dead when deputies entered their home to check on their welfare early Wednesday afternoon, Santa Fe County Sheriff’s Office spokesperson Denise Avila said. She said there was no indication that any of them had been shot or had other types of wounds.

His dozens of films included Oscar-winning roles in “The French Connection” and “Unforgiven,” a breakout performance in “Bonnie and Clyde,” a comic interlude in “Young Frankenstein," a turn as the comic book villain Lex Luthor in “Superman” and the title character in Wes Anderson’s 2001 “The Royal Tenenbaums.”

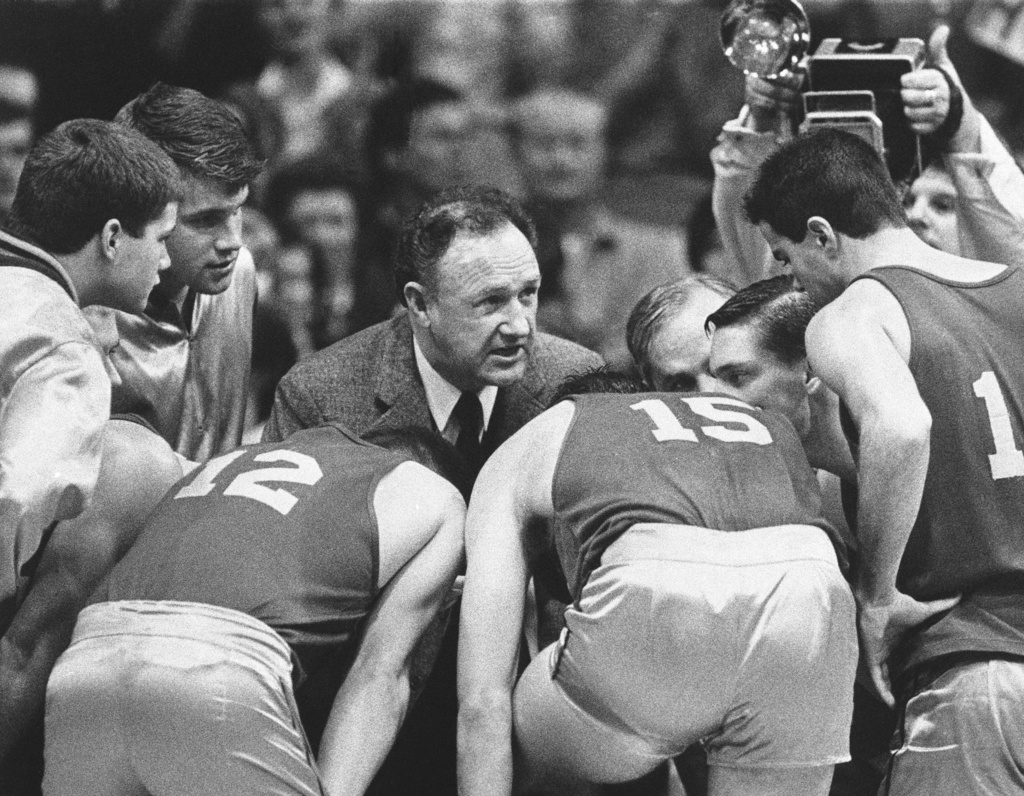

He seemed capable of any kind of role — whether an uptight buffoon in “Birdcage,” a college coach finding redemption in the sentimental favorite “Hoosiers” or a secretive surveillance expert in Francis Ford Coppola’s Watergate-era release “The Conversation.”

“Gene Hackman a great actor, inspiring and magnificent in his work and complexity,” Coppola said on Instagram. “I mourn his loss, and celebrate his existence and contribution.”

A plain-looking man with a receding hairline, Hackman held special status within Hollywood — heir to Spencer Tracy as an everyman, actor’s actor and reluctant celebrity. He embodied the ethic of doing his job, doing it very well, and letting others worry about his image. The industry seemed to need him more than he needed the industry. Beyond the obligatory appearances at awards ceremonies, he was rarely seen on the social circuit and made no secret of his disdain for the business side of show business.

“Actors tend to be shy people,” he told Film Comment in 1988. “There is perhaps a component of hostility in that shyness, and to reach a point where you don’t deal with others in a hostile or angry way, you choose this medium for yourself.”

He was an early retiree — essentially done, by choice, with movies by his 70s — and a late bloomer. Hackman was in his mid-30s when cast for “Bonnie and Clyde” and past 40 when he won his first Oscar, as the rules-bending New York detective “Popeye” Doyle in the 1971 thriller about tracking down Manhattan drug smugglers, “The French Connection.”

Jackie Gleason, Steve McQueen and Peter Boyle were among the actors considered for the role. Hackman was a minor star at the time, seemingly without the flamboyant personality that the role demanded. The actor himself feared that he was miscast. A couple of weeks of nighttime patrols of Harlem in police cars helped reassure him.

One of the first scenes of “The French Connection” required Hackman to slap around a suspect. The actor realized he had failed to achieve the intensity that the scene required, and asked director William Friedkin for another chance. The scene was filmed at the end of the shooting, by which time Hackman had immersed himself in the loose-cannon character of Popeye Doyle. Friedkin would recall needing 37 takes to get the scene right.

“I had to arouse an anger in Gene that was lying dormant, I felt, within him — that he was sort of ashamed of and didn’t really want to revisit,” Friedkin told the Los Angeles Review of Books in 2012.

Hackman also resisted the role which brought him his second Oscar. When Clint Eastwood first offered him Little Bill Daggett, the corrupt town boss in “Unforgiven,” Hackman turned it down. But he realized that Eastwood was planning to make a different kind of western, a critique, not a celebration of violence. The film won him the Academy Award as best supporting actor of 1992.

“To his credit, and my joy, he talked me into it,” Hackman said of Eastwood during an interview with the American Film Institute.

Eugene Alden Hackman was born Jan. 30, 1931, in San Bernardino, California, and grew up in Danville, Illinois, where his father worked as a pressman for the Commercial-News. His parents fought repeatedly, and his father often used his fists on Gene to take out his rage. The boy found refuge in movie houses, identifying with Errol Flynn and James Cagney as his role models.

When Gene was 13, his father waved goodbye and drove off, never to return. The abandonment was a lasting injury to Gene. His mother had become an alcoholic and was constantly at odds with her mother, with whom the shattered family lived (Gene had a younger brother). At 16, he “suddenly got the itch to get out.” Lying about his age, he enlisted in the U.S. Marines.

“Dysfunctional families have sired a lot of pretty good actors,” he observed ironically during a 2001 interview with The New York Times.

In 1956, Hackman married Fay Maltese, a bank teller he had met at a YMCA dance in New York. They had a son, Christopher, and two daughters, Elizabeth and Leslie, but divorced in the mid-1980s. In 1991 he married Betsy Arakawa, a classical pianist of Japanese descent who was raised in Hawaii.

When not on film locations, Hackman enjoyed painting, stunt flying, stock car racing and deep sea diving. In his latter years, he wrote novels and lived on his ranch in Sante Fe, New Mexico, on a hilltop looking out on the Colorado Rockies, a view he preferred to his films that popped up on television.

“I’ll watch maybe five minutes of it,” he once told Time magazine, “and I’ll get this icky feeling, and I turn the channel.”

___

Entertainment Writer Andrew Dalton in Los Angeles contributed to this report. Bob Thomas, a longtime Associated Press journalist who died in 2014, compiled biographical material for this obituary.